The Helsinki Accords were a set of non-binding agreements among North Americans, Europeans, and the Soviets signed fifty years ago on August 1, 1975. The accords sought to stabilize Cold War relationships between the West and the Communist East that had been on edge since 1947, when President Harry Truman set out the Truman Doctrine, a plan to contain communism. The Holy See was a signatory in Helsinki.

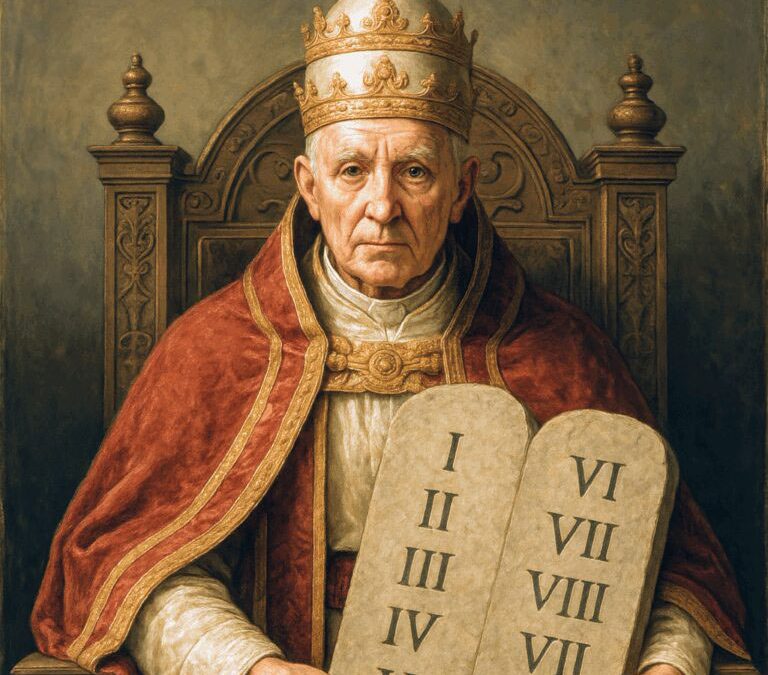

Pope Leo XIV recently reviewed the significance of Helsinki during a general audience in Saint Peter’s Square on July 30, 2025, noting the agreements on religious freedom and human rights. The Church agreed to the following language: “The participating States will respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief, for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.”

This apparent support for freedom of religion by Rome has a troubled counter narrative in the history of Catholicism. In the medieval period, religious dissent and heresy were rigorously suppressed through the most brutal violence, with widespread destruction of entire peoples such as the Waldenses, and the condemnation of individual heretics such as John Wycliffe, and the burning of Jan Hus and Jerome of Prague. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) anathematized Protestantism.

The Second Vatican Council (1963-1965) sought to modernize the Church with certain reforms, including affirming religious liberty; however, the Council of Trent was not rejected. Religious liberty in Catholicism is, to say the least, “complicated.” The Church holds mutually exclusive views. Like the characters in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, the animals on the farm are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. In Catholicism, all consciences are equal, but some consciences are more equal than others.

According to the Church, authentic consciences are aligned with truth and moral teaching, and it just so happens that the Roman Catholic Church determines what is true and moral. The Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “Conscience must be informed and moral judgment enlightened. A well-formed conscience is upright and truthful.”

Clashing ideas are sometimes said to be in “tension.” Tension is a handy word for glossing over contradictory concepts. The Church appears to see the human conscience as important and “free” to mature beyond bad information. Sooner or later, however, every conscience will come into unity with reality, as the Church understands it. The modern Church presents a gentle face and loving concern, but there is no doubt that someday all consciences will be properly formed, by force if necessary. A child might not agree that eating candy all day is a bad idea, but with maturity, and painful dental work, the child will be persuaded to moderate sugar consumption. Thus it is with all communities separated from Rome. The Church’s intention is to fix them all.

The problem with the Church’s understanding of truth is that it is self-generating. The Church is, in reality, no different than the culture at large, which believes in “create your own morality.” Catholicism, through reliance on Tradition, creates truth. Because the Church claims to depend at least partly on Scripture for truth, it can proclaim the part as the whole. But the mix of Scripture and Tradition cancels out the concept of the Bible Alone. Truth and error are still error. If Scripture and Tradition are in harmony, then they together are truth. But if they differ, then the harmony, or truth, disappears.

The world is a mass of confusing philosophies, religions, and ideologies. Unity is possible only through a determination to find some sort of common ground. Only then can chaos turn to peace. The ecumenical movement is Rome’s method of finding unity. Since Romanism is the single largest faith on earth, it is natural that Catholicism would proclaim itself as the bearer of Truth. Catholicism is the “one true religion” (as the Catechism claims).

The Catholic way of viewing unity is growing in influence, and it appears to cross denominational lines in subtle ways. Here are a couple of recent examples.

Professor Stephen Meyer, a noted creation scientist, gave a talk in 2023 on the 40th anniversary of a speech by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn called “Men Have Forgotten God.” Meyer entitled his own talk, “The Real Reason Our Culture Is Falling Apart.” Solzhenitsyn remembered the old people of his childhood bemoaning the coming of communism and the loss of belief in God. They blamed the disasters of communism on atheism. Meyer was raised Roman Catholic, but is apparently simply Christian.

Meyer uses Solzhenitsyn’s example to critique current American culture. The nation is in a moral decline, Meyer notes. Fewer people believe in God, traditional religion is struggling, crime is rising, and gender ideology is taking root. Could it be that our decline is rooted in godlessness? he asks.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature and prisoner for many years in the Soviet Gulag, became an icon of dissent. He was born into the Russian Orthodox Church, became a confirmed atheist, but then returned to Eastern Orthodoxy. His analysis of Western culture opened his mind to the value of traditionalism.

When he returned from exile in the United States to Russia in 1994, he was shocked by the changes he observed. He said, “Russia is living through an orgy of vice and immorality.” Solzhenitsyn’s reputation in Russia as a great moral leader soon lapsed into boredom with his emphasis on traditional values and religion. Russia didn’t want to hear what the great man had to offer.

David Brooks is a well-known author and columnist. Raised a Jew, Brooks now identifies as Christian. He was once active in conservative politics, but is a very moderate figure in today’s Republican politics. In a recent column (July 31, 2025), Brooks echoes Solzhenitsyn and Meyer. His essay is entitled “The Crucial Issue of the 21st Century.” Donald Trump is no believer in small government or decentralized power. Trump exists in an America that thinks of itself as fundamentally broken. “America’s social order has fractured,” Brooks writes. People are no longer hopeful, trusting, or forward looking.

Brooks’s solution? Americans need order. He writes, “To put it another way, all humans need to grow up in a secure container, within which they can craft their lives. The social order consists of a stable family, a safe and coherent neighborhood, a vibrant congregational and civic life, a reliable body of laws, a set of shared values that neighbors can use to build healthy communities and a conviction that there exists moral truth.”

When we examine what Meyer, Solzhenitsyn, and Brooks each say, we see a surprising conformity. However, it is a conformity without specific content. We simply hear Fiddler on the Roof‘s main character Tevye, a Jewish patriarch in the old Russian empire who can’t cope with social change. A daughter resists an arranged marriage. His cry? Tradition!

Roman Catholicism offers something here. A history of changelessness. Of order. Of authority. Of morality. What kind of morality? Tradition.

The Bible foretells that humanity will reach a point of despair, a despair that draws it to the most outrageous set of religious claims of all time. Rome/Babylon is large and extremely powerful. It earns the admiration of the entire world. In fact, the world worships the “beast.”

Tradition will not save the world. Worship of the true God of the Bible will lead to salvation. Rome offers an altered law, a false Sabbath that it will foist on the world. The worshipper of the beast will “drink of the wine of the wrath of God” (Rev. 14:10). God is calling, “Come out of her, my people.”